It is arguably more challenging for retail investors to spot mispriced opportunities. Unlike the most promising growth stocks, underappreciated companies rarely make the headlines, and when they do, it’s often for negative reasons.

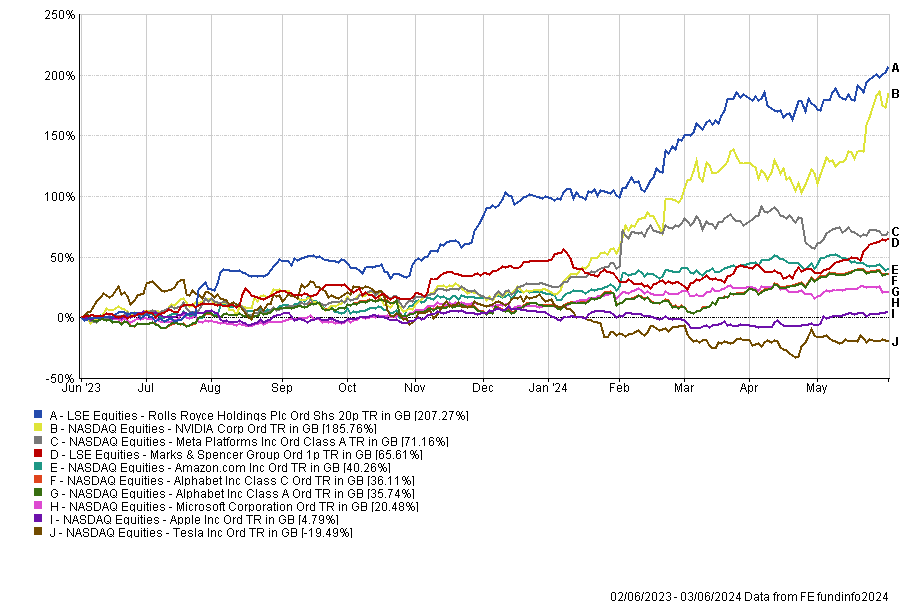

Yet, they can be a cost-efficient way to make profits. For instance, buying shares in the then-unloved and therefore cheap Rolls Royce one year ago would have delivered better returns in sterling terms than investing in any of the expensive and well-known Magnificent Seven, including Nvidia.

Likewise, Marks & Spencer’s recovery has delivered returns exceeding those of most US artificial intelligence beneficiaries, and at a cheaper price.

Performance of stocks over 1yr (in sterling)

Source: FE Analytics

So how do professional contrarian investors identify these turnaround stories?

According to FE fundinfo Alpha Manager Alec Cutler, who runs Orbis Global Balanced and Orbis Global Cautious, there are plenty of signs in publicly available information that can suggest an opportunity.

These signs could include fearful headlines or headlines suggesting hope after a long period of dread, broker commentary that misunderstands the business, or commentary starting to connect the dots after a long period of not getting it, a falling share price, or a share price that stops declining even when the company reports tough conditions.

He said: “As a contrarian, you never really know what the catalyst is going to be. You try and find things that are cheap, where you can see a contrarian case. But you never really know what the thing will be that shifts the market’s view.”

An example Cutler gave is electricity infrastructure stocks. While he did not know what the catalyst would be at the time of purchase, they benefited from the artificial intelligence rally, as this technology requires a lot of electricity.

“You can pay up for Nvidia, or you can buy an electric utility of all things. It’s pretty cool to see that,” he said.

However, Dmitry Solomakhin, portfolio manager of Fidelity FAST Global, warned that contrarian investing is a time-consuming process with no “hard and fast rules”.

He structures his approach in three steps. The first is to find a business that is fundamentally of good quality but may have been mismanaged or gone through operational or financial issues. Then it is important to ensure the company acknowledges these issues and is willing to address them. Finally, the management and the board need to be capable of executing the necessary changes.

Rolls Royce, which remains his largest holding today, “was lacking cost and financial discipline, but it is now being fixed”, Solomakhin said. “There have been very significant improvements in cash flows and financial returns and it now in an even stronger competitive position today.”

Due to the nature of contrarian investing, Tom Matthews, co-manager of the JOHCM UK Dynamic fund, emphasised that this investment style requires both discipline and patience.

Discipline is needed when selecting which assets have the potential to be turned around. Moreover, investors must ensure they are paying the right price for the expected future cashflows, with an “acceptable margin of safety on top”.

As for patience, he believes investors should hold back until a new management team reveals a strategy focused on unlocking value and the benefits of the turnaround start to accrue to shareholders.

Matthews added: “At UK Dynamic, our holding period for stocks is often well over five years. Good things do come to those who wait!”

What financial ratios can investors use?

One of the first things James Henderson, portfolio manager of Henderson Opportunities and Lowland Investment Company, considers when looking for a mispriced opportunity is a company’s sales volumes.

“Firstly, it’s a good indicator of size – where market cap tends to fluctuate, sales volume provides us with a solid number to start from. It is particularly important for us because it gives us an indication of existing demand,” he explained.

“When a company is in trouble, it might not be making a proper margin on its sales, or it might even be making a loss, but the sales number tells us what scope there is for improvement of those margins once other issues have been addressed. This helps focus a company on the changes they need to make to return to proper profit margins.”

The main metric Henderson uses is the enterprise value-to-sales ratio, which indicates how much it would cost to buy a company in the context of its sales.

Debt is another factor that Henderson considers.

He said: “Often in these cases, debt is too high so we need to understand how it is going to be paid down. We then need to assess whether a company is going to invest in its own products to improve their offering sustainably. So, we look at the debt position when we make the initial investment, and we have to see a path from there to bring it down.”

To identify contrarian opportunities, Solomakhin relies on free cash flow, which is a measure of profitability representing the remaining cash after capital expenditures have been subtracted.

He said: “I look at the normalised free cash flow the business should be able to generate three to five years out if the turnaround is successful. If it offers over 15% free cash flow yield to enterprise value on these normalised numbers, it is quite attractive.”

Beware of value traps

Contrarian investing is not without risk as turnaround stories might never materialise.

Mark Landecker, portfolio manager of Nedgroup Contrarian Value Equity, explained: “Value traps occur when a company’s cashflows fail to inflect. There are two clear cases when this can occur.

“First, a company’s end-markets are too structurally challenged and its revenues and cashflows collapse faster than it is able to re-allocate capital to new, higher returning parts of the business.

“Second, a company’s starting debt position or transformational capital investment requirements are too high, meaning that cashflows never reach inflection point.

“Any combination of these can lead to the equity value of a company being significantly diluted as investors are required to inject further capital.”

Solomakhin added that misses are part and parcel of investing in contrarian opportunities.

“Given that I only look at challenged businesses with turnaround potential, any mistake that I make will almost certainly be a value trap. If I am good, then my single stock ‘hit rate’ will be around 54-55%, which means in 45-46% of cases I will be involved in value traps,” he pointed out.

An example of a stock that did not live up to his expectation is Tripadvisor. He explained that the company used to have a strong competitive moat due to the large user base and a database of consumer reviews. However, it then tried to compete directly against its own customers, such as Booking.com or Expedia, and failed. Moreover, the company’s competitive moat has weakened over time.