Government debt levels have surged across advanced economies and they’re now a hot topic in politics and financial markets alike. Politicians were quick to borrow during the global financial crisis and pandemic to support their economies but they have struggled to reduce debt in the good years. After almost a decade of super-low interest rates, higher borrowing costs are biting hard.

For investors, this matters because government bonds are a foundation of the financial system. Rising debt and higher borrowing costs can ripple through markets affecting inflation, growth and long-term returns across all asset classes.

How high is government debt and how did we get here?

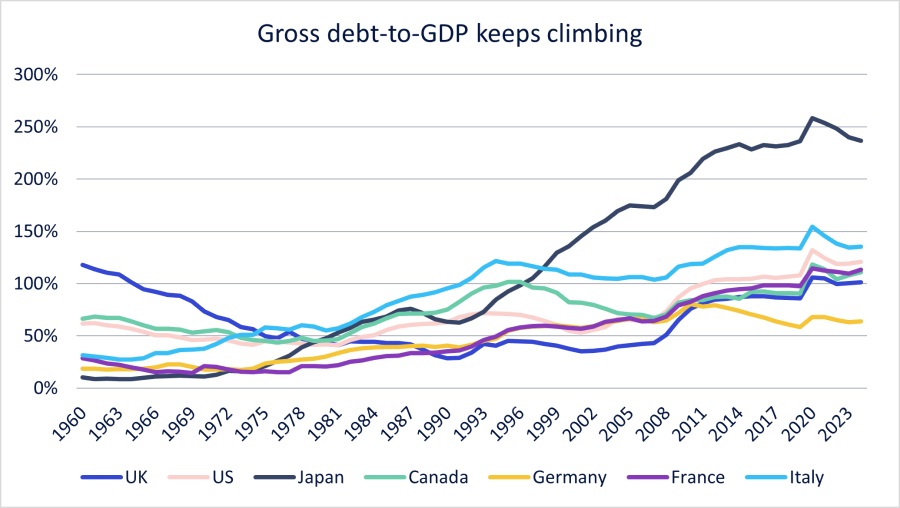

Debt has been climbing relative to GDP for at least the past two decades across most major economies. According to the IMF, gross US government debt has risen from around 55% of GDP in 2000 to more than 120% today.

The UK has followed a similar path, moving from about 35% to over 100% over the same period. As the chart below shows, this isn’t just a UK or US story. Across almost all G7 economies, debt-to-GDP ratios have ratcheted higher with each crisis and the trend has been persistently upward.

Source: IMF Public Finances in Modern History Database, LSEG, Rathbones; data to 2024, central government used instead of general government until 1970s in some countries.

People often lament spendthrift governments and irresponsible politicians as the reason for this rising indebtedness. While some better decisions could have been made over the years, it’s also true that it has become more difficult for those in power to manage public finances.

That’s because the underlying pace of economic growth across the world has slowed, the ‘peace dividend’ from lower military spending has run dry, interest rates have stopped falling (and started rising) and populations are ageing.

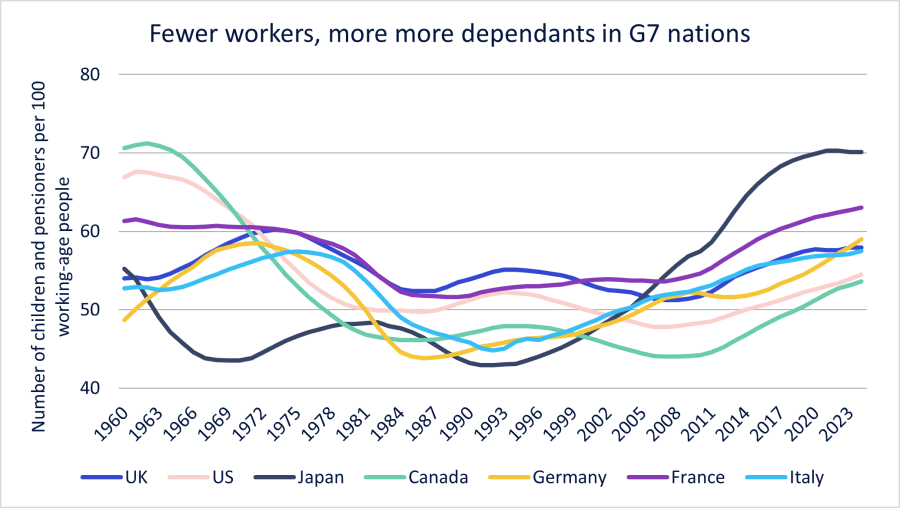

Demographics are particularly important to understanding the demands on government spending. For much of the second half of the 20th century, the share of dependants — children and pensioners — relative to the working-age population was falling.

That eased pressure on public finances as dependants tend to receive more in benefits or public services than they pay in tax, whereas the opposite is true for most workers.

But the trend has reversed. The chart below shows dependency ratios have been rising across the G7, in some cases since the 1990s. Each worker is supporting a greater number of dependents. This shift is likely to continue.

Source: LSEG, Rathbones; data shows the number of children and pensioners for every 100 people of working age (known as the dependency ratio) to 2024.

The size of debt isn’t so much the problem as turning off the tap

These forces mean public finances are likely to remain stretched for the foreseeable future. And governments may increasingly rely on debt markets to bridge the gap, as this is often politically preferable to cutting public spending or hiking taxes – as we’ve seen recently both here in the UK and abroad in France and America.

While the headlines often suggest Britain’s debt burden is especially worrying, the data tells a more balanced story. UK government debt is high, but depending on the measure used, it’s the second or third-lowest in the G7, relative to GDP.

Looking more broadly, the UK is certainly not an outlier relative to other advanced economies. Some countries, such as Japan, Italy and the US, are carrying significantly larger burdens.

The risk of a sudden debt crisis – where borrowing costs spiral and governments lose access to funding – is much lower for advanced economies today than for the emerging markets that have suffered debt crises in the past.

One key reason is that countries such as the UK, US and Japan borrow in their own currencies, which gives central banks more options to step in if markets wobble.

We’ve already seen this in practice. The Bank of England intervened in 2022 to calm gilt markets after the mini-Budget, while the US Federal Reserve has created facilities to limit forced selling of treasuries (US government bonds). These measures reduce the risk of a short-term funding crisis.

So what are the real risks?

Avoiding an acute crisis doesn’t mean there are no costs. If governments keep borrowing heavily, we may see ‘financial repression’ – policies that hold down interest rates or channel savings into government debt.

This has happened before. After the Second World War, the UK’s debt was around 270% of GDP and the US’s 120%. Both countries artificially capped borrowing costs and directed savings into government bonds.

While this helped reduce debt, it acted as a hidden tax on savers, with returns on deposits and government debt falling below inflation for long periods.

While we don’t expect a full repeat of this post-war experience today, we do think a lighter form of financial repression is possible in the years ahead. If we’re correct, we should expect higher and more volatile inflation, given that central banks will have less free rein to keep it under control.

Slower economic growth is also possible, either because of higher inflation, or if measures to artificially supress interest rates lead to an inefficient use of resources across economies.

To prepare for this, we recommend that our investment managers’ portfolios contain:

- Shorter-duration bonds, reducing exposure to long-dated bonds that could be hit hardest by higher inflation, while benefiting from relatively high yields.

- Diversifiers such as gold and strategies that tend to perform better in inflationary environments.

- Balance across assets, keeping exposure to equities while being mindful that slower growth could weigh on returns.

- A bias towards quality, highly profitable equities, which usually withstand spikes in inflation better than their peers.

By incorporating these elements, we aim to keep portfolios resilient to a more challenging environment, without losing sight of the opportunities that come from market dislocations.

Adam Hoyes is a senior asset allocation analyst at Rathbones. The views expressed above should not be taken as investment advice.