Private credit has grown remarkably over the past decade. What was once a relatively niche corner of the alternatives universe has become one of its largest and fastest-growing segments.

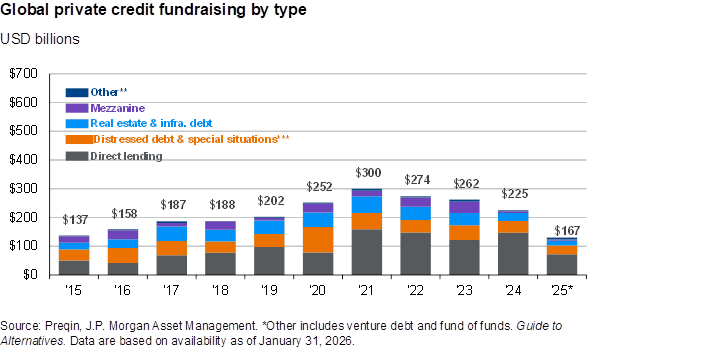

Fundraising has exceeded $1trn over the past five years, assets under management have grown at 14.5% per annum and private credit has become a core allocation for many institutional portfolios.

But rapid growth rarely goes unquestioned. The pace of expansion, combined with a handful of high-profile credit events over the past year, has inevitably raised concerns.

Critics have asked whether private credit has grown too large, too fast – and whether the attractive returns of the past decade can be sustained.

To answer those questions, it is worth considering why private credit grew so quickly in the first place, how the opportunity set has changed and what investors should focus on as the asset class enters a more mature phase of its cycle.

Why has private credit grown so fast?

Private credit’s rise is best understood through the lens of shifting supply and demand in corporate lending. On the supply side, the post-global financial crisis regulatory regime materially increased capital requirements for banks, making it less economical to lend to riskier small and mid-sized companies. Private credit funds stepped in to fill that gap.

Increased institutional allocations further reinforced the supply shift. Through much of the 2010s, structurally lower interest rates pushed institutional investors to private credit in the search for higher yield.

Pension funds and insurance companies found private credit’s floating‑rate coupons, stable cashflows and yield premium over public credit particularly attractive.

As allocations grew, so did the lending capacity of private credit funds, enabling the market to serve more borrowers. Strong performance then amplified this cycle: over the past decade, private credit delivered attractive risk-adjusted returns with lower volatility and smaller drawdowns than many public credit indices.

That track record supported continued fundraising, further deepening the pool of available capital.

On the demand side, private equity was pivotal. As private equity expanded globally, demand for flexible, non‑bank financing rose alongside it.

Direct lending became an integral part of the buyout toolkit, financing acquisitions, refinancings and secondary transactions. This preference increased demand for private credit relative to traditional bank loans, especially in complex or time-sensitive deals.

Is private credit still attractive today?

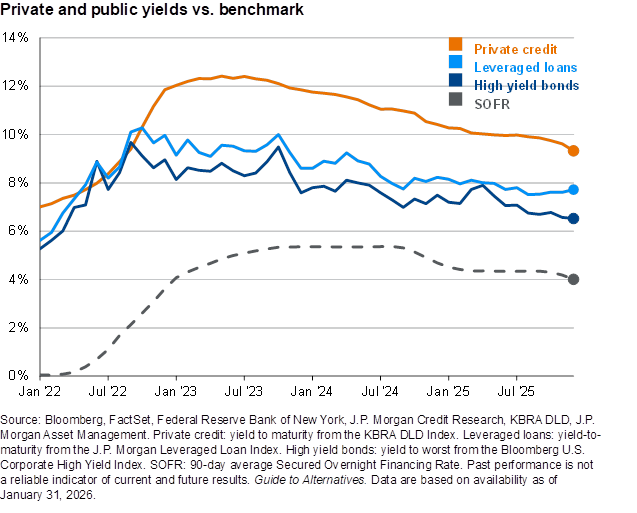

Private credit yields are lower today than they were a few years ago but remain at elevated levels. Base rates have come down, while the competition to deploy the large stock of dry powder has put downward pressure on spreads.

Even after compression, private credit yields today are 9.3%, around 160 basis points over broadly syndicated leveraged loans, and around 280 basis points over high yield bonds.

While yields are high in absolute terms, investors must focus on whether they are currently being compensated for taking additional risk in private credit today.

Two considerations make me comfortable that the answer to that question is yes.

First, a combination of high yields and seniority in capital structure creates decent protection against losses. At today’s yields, we would need to see default rates rise over three times their current levels to see negative total returns, assuming reasonable assumptions about leverage and recovery rates.

Second, to fully erode the additional yield premium that private credit offers over high yield, default rates in private credit would need to rise by roughly six percentage points above those seen in public markets, assuming relatively conservative 50% recovery rates. That is a meaningful cushion.

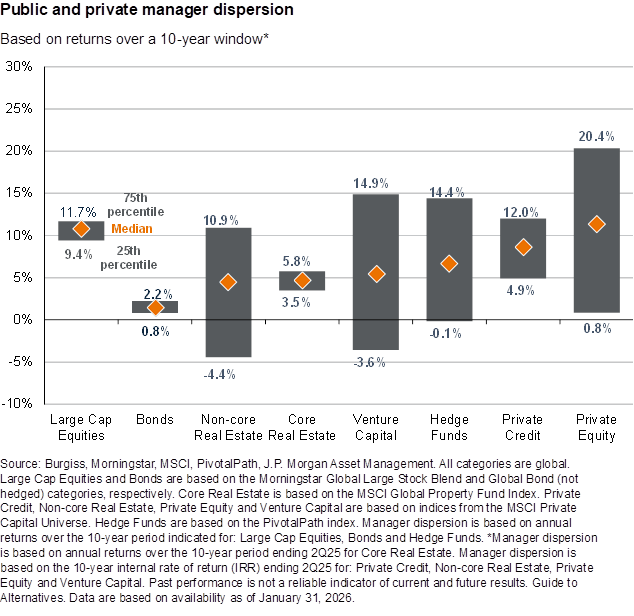

That’s not to say there isn’t risk in private credit. The low default rates of the past decade were supported by lower interest rates. With rates now higher, debt servicing costs are higher and when we do see an economic slowdown dispersion is likely to increase – both across managers and across vintages.

So how should investors allocate to private credit today?

First, investors need to place greater emphasis on selectivity and risk management than in the past. Reducing concentration risk, avoiding aggressive leverage structures and maintaining diversification across vintage years are increasingly important in mitigating downside risk.

Structural protections – such as strong covenants, seniority in the capital structure and conservative documentation – are also going to matter far more when we enter a challenging environment.

The gap between top-quartile and bottom-quartile managers is already wide and there is little reason to believe it will narrow. On the contrary, as weaker loans come under pressure, differences in portfolio construction and risk discipline will become more visible.

Active selection – informed by track record, team stability, sourcing capabilities and alignment – will be a key driver of alpha over the next cycle.

Second, investors should broaden beyond direct lending. Direct lending remains the core of the asset class, but it is no longer the only source of attractive risk-adjusted returns.

Many investors are increasingly looking to complement traditional direct lending with exposure to real estate debt, infrastructure debt and special situations.

These strategies can offer different risk drivers, longer duration or stronger asset backing, helping to diversify portfolios and reduce reliance on a single segment of the credit market.

In a more competitive environment, such diversification can play an important role in improving portfolio resilience.

Conclusion

Private credit has entered a more mature and demanding phase of its evolution. The era of easy growth, abundant spread and uniformly strong performance is likely behind us. But that does not mean the opportunity has disappeared.

Instead, the asset class is transitioning from rapid expansion to greater differentiation. Returns will increasingly be shaped by manager skill, structural discipline and thoughtful portfolio construction rather than market beta alone.

For investors willing to be selective, private credit still has a valuable role to play in diversified portfolios. The challenge now is not whether to allocate, but how.

Aaron Hussein is global market strategist at JP Morgan Asset Management. The views expressed above should not be taken as investment advice.