The concept of a star manager has increasingly fallen out of favour, particularly following the Neil Woodford debacle in 2019. The lack of star names has led to the rise of the team-based approach, with fund groups adding more co-managers to balance out any single-person risks.

But star managers still have a role to play. Recent evidence of this came when Ben Whitmore announced his departure from Jupiter earlier this year. At the time Hargreaves Lansdown removed the Jupiter Global Value Equity fund from their wealth shortlist.

This decision was attributed to Whitmore’s departure, with senior investment analyst Joseph Hill reiterating Hargreaves’ conviction in the fund had been with Whitmore. The funds run by the manager have also been hit with significant outflows since the announcement was made.

Other examples of star names still in the industry include Terry Smith and Nick Train, responsible for the £23.6bn Fundsmith Equity and £4.1bn Lindsell Train Global Equity portfolios respectively.

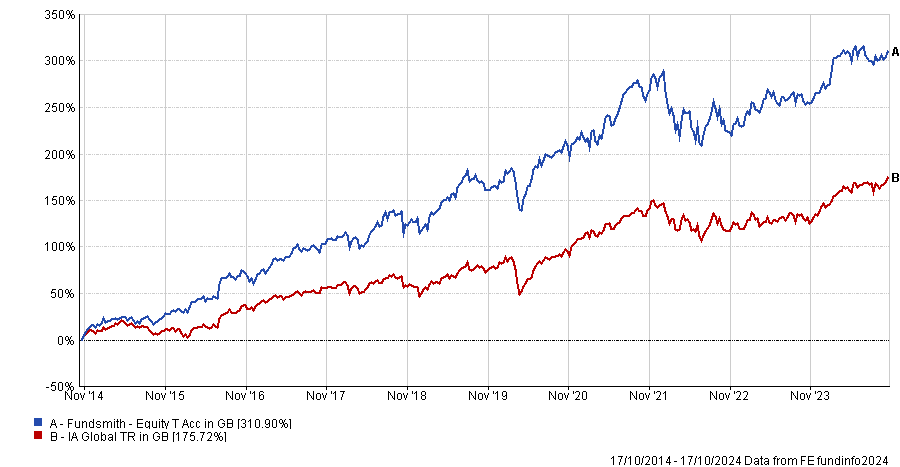

Over a decade, Fundsmith Equity enjoyed a rise of 310.9%, the eighth-best performance in the IA Global sector, which currently has 562 different portfolios. This resulted from several first-quartile efforts, including top 10 results of 23.3% and 15.7% in 2014 and 2015.

Performance of fund vs sector over 10yrs

Source: FE Analytics

It is featured on the Square Mile Academy of Funds, and this is partially because of Smith's profile and expertise.

Analysts at Square Mile said: “The fund has many qualities. In Terry Smith, it benefits from a charismatic manager who together with Fundsmith’s head of research Julian Robins, has developed a product that has a clearly defined philosophy and process.”

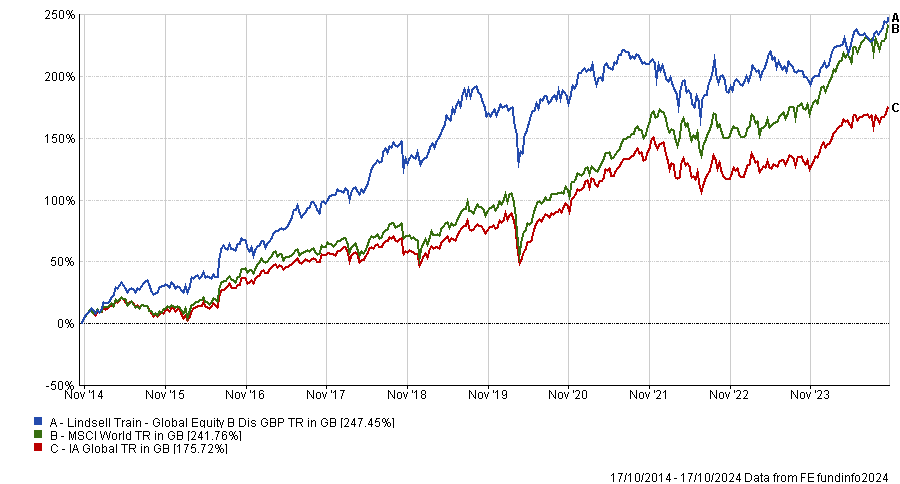

The Lindsell Train fund has enjoyed a similarly impressive record, with a return of 247.5%, putting it in the first quartile of the sector over the past decade. It achieved particularly impressive results in 2015 and 2018, when it was up by 19.5% and 11.1% respectively, the third- and second-best results in the peer group.

Performance of fund vs sector and benchmark over 10yrs

Source: FE Analytics

The problem with relying on concentrated managers, however, is that they are volatile, with the best performers over one period unlikely to outperform over the next.

This is even true for Smith and Nick, with both of their portfolios failing to replicate their top-quartile results in more recent periods. For Lindsell Train, a performance of 27.9% has caused it to languish in the bottom quartile of the peer group over five years.

Craig Baker, manager of the £4.9bn Alliance Trust, said: “In recent years, it has been almost impossible to be at the top in one three-year period and also be at the top in the next three-year period.”

“You may say, ‘I have a long-term perspective I can write this off’. I assure you that you won’t. The human psyche won’t let you. If a manager is doing incredibly badly, it is difficult to stick with them or justify giving them more money.”

Another issue with the ‘star manager’ mantra is key person risk, said Paul Angell, head of investment research at AJ Bell, who noted earlier this year that there are still “plenty of funds” with this problem, despite the move towards more team-based approaches.

However, despite this, Dan Higgins, chief executive officer at Majedie Investments said now is a great time for managers to make a name for themselves, as choppy markets tend to lead to better performance from active portfolios.

“I think the opportunities for the best active managers to add value is better today than it has been since I started my career in the early 1990s,” he said.

“I think the world’s history doesn’t repeat, but it rhymes. I think we’re going back to a world in which it’s going to be possible for managers to differentiate themselves”.