Next year the AIM market turns 30, but if there is a party will anyone turn up? Despondency and concern from the investment community about smaller companies has seldom felt greater in the many years I have been managing money.

Worries about the general outlook for the UK are now compounded by specific concerns for some AIM investors that the tax exemptions might be removed or reduced in the coming Budget.

We can talk more about tax shortly, but first why AIM matters, and why a sensible Chancellor will do everything possible to ensure the health of this market.

AIM – formerly the Alternative Investment Market and a sub-market of the London Stock Exchange – was launched in June 1995 with just 10 companies. What makes it distinctive is the lower regulatory burden on companies listed there. This puts more onus on the investor to conduct detailed due diligence but it gives young, growing companies a route to capital without overburdening them with crippling compliance and legal costs.

From inception to September this year, AIM had helped more than 4,000 companies raise over £135bn, with nearly £87bn of that as follow-on capital to help them grow further.

And many have done. Take specialist insurer Hiscox. In the early 1990s Lloyds of London was running out of capital. The ‘names’ who had traditionally provided capital with unlimited liability had experienced severe losses.

What was needed was a new structure supported by companies with limited liability. But they themselves needed capital. AIM provided this and we invested in several. It has been very worthwhile, with some being taken over and others, like Hiscox, growing phenomenally.

London’s status at the heart of the global reinsurance industry owes much to AIM and the role it played in rejuvenating the industry.

Today there is a need for a new generation of alternative energy companies. With little in the way of trading records these early-stage businesses have relied on AIM to raise the capital they need. ITM and former AIM stock Ceres, for instance, have both raised money on multiple occasions to finance their development. I believe that one day we will look back and appreciate AIM’s vital contribution in the journey to renewables.

The London Stock Exchange has tried to put a number on AIM’s value to the UK. Last year, research it commissioned from Grant Thornton found that in 2023 alone, UK companies admitted to AIM contributed £68bn to the UK economy through direct, supply-chain and induced impact. They have paid £5.4bn to the Exchequer.

Hiscox and Ceres are now on the main market. Other familiar names have followed that path, like Asos and Melrose. But many significant companies remain on AIM. Jet2 is now a £3bn company – bigger than any FTSE 250 business. And 28 companies on AIM are now worth over £500m.

One example is laboratory instrument business Judges Scientific – admitted in 2005 and now with a market capitalisation of £630m. I stupidly thought it was too expensive a few years ago. On admission the shares were about a pound. Today they are nearer £100.

But I have enjoyed other successes, too. I have held defence technology company Cohort for many years – it was admitted in 2006 with shares at £1.48. Today they are nearer £9.

There are downsides for investors too, of course. It can take patience, waiting for a company to really build the foundations for success. Many fail. Patisserie Valerie left a bitter taste in the mouth for many investors when it collapsed following a fraud in 2019. This year alone 14 companies have been admitted, but another 72 have been cancelled – de-registered, bought out or folded.

Few move from AIM to the main markets but to be fair, not every company aspires to do so. For companies with a degree of family ownership, for example, the business property relief that comes with being on AIM, protecting the investment from inheritance tax (IHT) on death, can make it a sensible long-term home.

And that brings us to the thorny issue of tax. It has been estimated that if the IHT relief was withdrawn it could lead to a 30% drop in share prices.

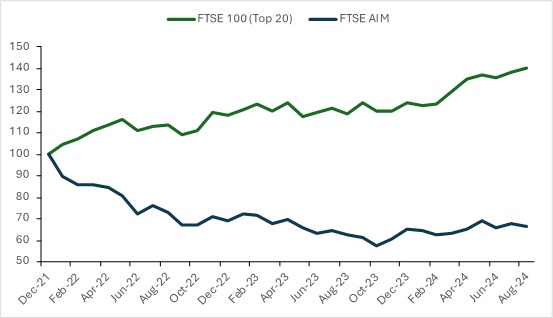

To me, much of that risk looks priced in already. Stand a mirror on the horizontal axis of a chart showing the returns of the top 20 companies in the FTSE 100 since the beginning of 2022 and you will see in the reflection a line going almost exactly the opposite way. That’s AIM. The FTSE is up 39.9% since then; AIM is down 33.6%.

FTSE 100 vs AIM

Source: Janus Henderson Investors

Total capital raised by AIM companies fell by more than 70% last year on the market’s 20-year historic average. And the number of companies on AIM has fallen from 819 at the end of 2020 to 695 companies, valued at £72bn today. So where next for AIM?

This market still plays a huge part in the economic life of the UK. I cannot see that changing without dire consequences.

Investors can easily wander into an echo chamber of gloom and depress each other out of an opportunity. I have the advantage of getting out to meet the managers of many AIM-listed companies and so often come away enthused by the progress they are making.

An economy is driven not by Budget pronouncements but by innovation and hard work. My visits and meetings suggest the current climate of gloom is misplaced.

Falling interest rates should help trigger consumer spending and encourage corporate investment that delivers growth. It might also encourage investors to switch from cash to equities.

For those wise enough to take a long-term view, who do their research, buy shrewdly, diversify to reduce risk and are prepared to be patient, AIM is rich in opportunity – perhaps as much as at any time since its launch.

We may get to realise some of that opportunity the other side of the Budget, if it proves less contentious than the market currently fears. It does not take much to change the mood. By the time AIM hits 30, I hope we will have something to celebrate.

James Henderson is co-manager of the Henderson Opportunities Trust, Lowland Investment Company and Law Debenture. The views expressed above should not be taken as investment advice.