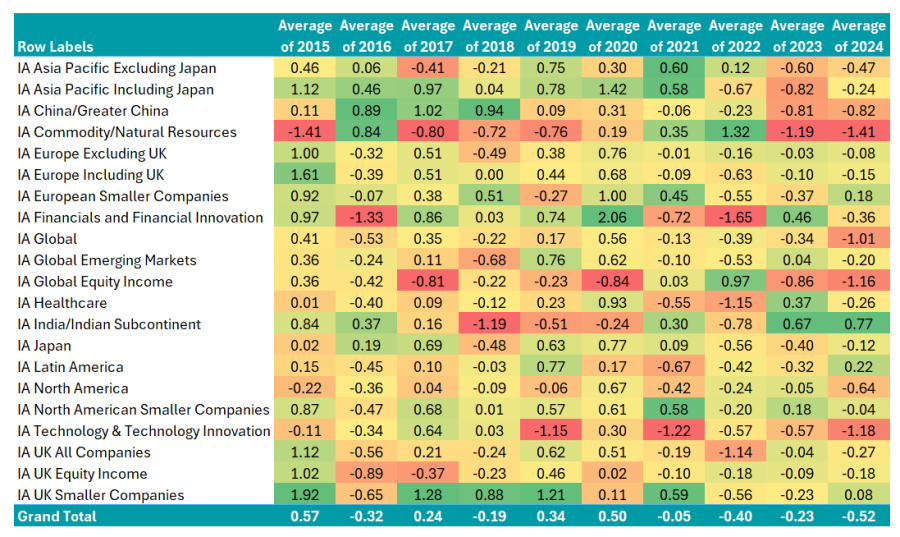

Active managers suffered their worst year for skill in a decade, Trustnet research has found, with the average information ratio of active managers falling to -0.52.

It topped 2016, when the election of Donald Trump and the Brexit referendum shook the market, as well as 2022, when rising inflation and interest rates led to poor performance for many active funds.

The information ratio is an expression of the success of a manager ‘tilts’ away from the benchmark and is seen to differentiate between skill and luck in a fund's performance. It is found by measuring a portfolio's risk-adjusted returns compared to the benchmark, considering its excess return and volatility.

We examined the information ratio of active funds in the 21 Investment Association sectors between 2015 and 2024, compared to the most common benchmark.

Information ratio of IA funds over the past 10yrs

Source: FinXL

Four peer groups had a positive information ratio in 2024: IA UK Smaller Companies, IA Latin America, IA India/Indian Subcontinent and IA European Smaller Companies.

Market concentration

For Zachary Ryan, senior fund analyst at FE Investments, “concentration is the key point” to explain why active managers had a poor 2024.

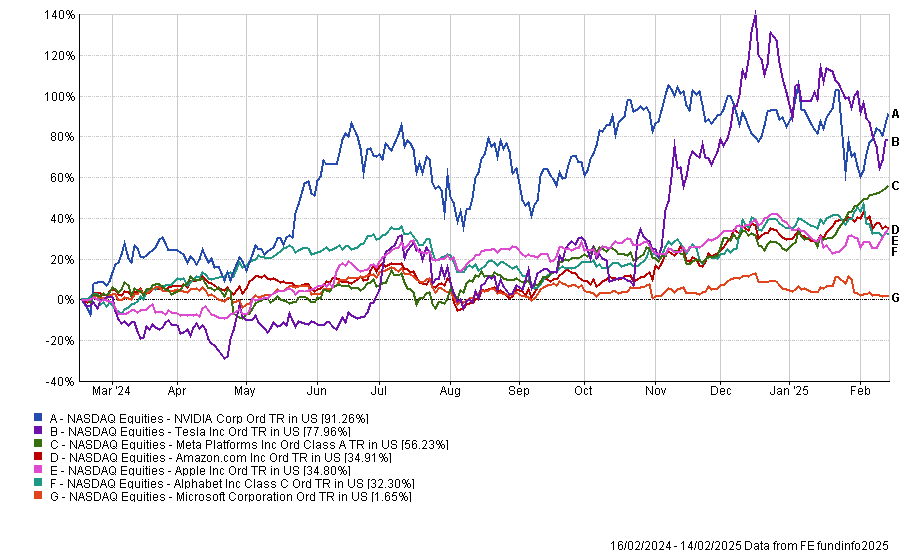

Markets have become focused on a select number of top-performing stocks, such as the Magnificent Seven (Alphabet, Microsoft, Google, Nvidia, Apple, Tesla and Meta). These now represent a quarter of the global index and delivered exceptional returns for investors last year.

Performance of the Magnificent Seven over past year

Source: FE Analytics

Ryan explained the 5/10/40 rule of portfolio construction could have something to do with this. It prevents managers from holding more than 10% of their fund in individual securities, while the total amount for holdings above 5% may not exceed 40% of the portfolio.

When the largest constituents of the index outperform, this rule prevents active managers from holding these stocks to the same level as an index, which does not have to adhere to these stipulations.

Rob Morgan, chief analyst at Charles Stanley Direct, said this meant even growth funds struggled last year because many “eschew the Magnificent Seven” to avoid adding significant concentration risk.

He added: “Fund managers will rightly baulk at running a fund with such a concentrated portfolio, but it means when a few of the heavyweights in the index do very well, it is almost impossible for an active fund to keep up.” Indeed, only a third of actives beat passive competitors last year.

Morgan argued that this explained the negative information ratios of the IA North America, Global and Global Equity Income sectors, where these stocks are the most dominant.

For Simon-Evan Cook, manager at VT Downing Fox, this level of market concentration is “in many ways far worse than what we saw in 2000, which was a nightmare for active managers”.

The dominance of the Magnificent Seven has caused small and mid-caps to struggle – an area where active managers usually find their most attractive opportunities.

Evan-Cook concluded: "Active managers are underweight mega-caps in a market that loves mega caps”.

This phenomenon is far from US-only, however, with mid and smaller-sized companies struggling in the UK and Europe as well.

How can active managers outperform?

For this to change, fund selectors argued that the market needed to broaden out. Morgan said: “A market where winners come from different sectors, or where a broader range of stocks do well, should favour active managers more”.

He identified India as an example of this trend. It was 2024's big winner with an information ratio of 0.77, which Morgan explained was because it was a vibrant stockpicking market with fewer analysts but a significant difference in company quality. This offered many opportunities for sufficiently skilled active managers to differentiate themselves.

It is also a sector where small and mid-caps have thrived, with several active managers holding companies lower down the market capitalisation spectrum.

A “wobble amongst the top dog stocks” and a better performance from small and mid-caps was the “obvious trigger” for a resurgence in active managers results, he concluded.

Evan-Cook agreed and said active managers “need the market’s biggest stocks to stop outperforming or, even better, to start underperforming”.

For example, the FTSE All Share is heavily weighted at its top end towards large banks and fuel companies such as BP and Shell. Both areas have risen as interest rates have gone higher and the oil price has rocketed. However, he explained that the IA UK All Companies sector was a market where many active managers hold small and mid-cap names.

By prioritising small and mid-caps, the IA UK All Companies sector beat the FTSE All Share when these large-caps wobbled, achieving positive information ratios in 2015, 2017, 2019 and 2020.

“Simply by avoiding those big names, active managers were getting a head start”, Evan-Cook argued.

However, big banks and fuel companies rallied in 2022 because of increased inflation and higher interest rates. “Lo and behold, active managers have struggled”, he added, demonstrated by the recent negative information ratios of the IA UK All Companies Sector.