Traditional government bonds will not provide the ballast to a portfolio they have historically, according to Peter Kent, co-head of fixed income at Ninety One, who warned investors that “asset allocation approaches need a reboot”.

The main difference this time around is the rationale behind market volatility. In past crises, such as in 2008, the issue was demand-driven.

This made predicting the future much easier, he said, as analysing demand shocks, and policy responses to them, is “relatively less complex than analysing supply shocks”.

Typically, when growth fell, lower inflation would follow, meaning fixed income behaved well as a defensive asset.

However, in recent years the nature of shocks hitting the global economy has changed. Brexit, Covid, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and trade tariffs are all supply-sided, which makes forecasting much more difficult.

“These are exceptionally hard to quantify and have resulted in growth and inflation moving in opposite directions – i.e. lower growth and sticky inflation. That has led to higher correlations between defensive and cyclical assets; in this context, developed market bonds have been less able to shield investors from equity market losses,” said Kent.

“Put another way, the shift from demand to supply shocks has changed the nature of interest rate risk and its relationship with risk assets, meaning it’s not as helpful for managing a balanced portfolio as it used to be.”

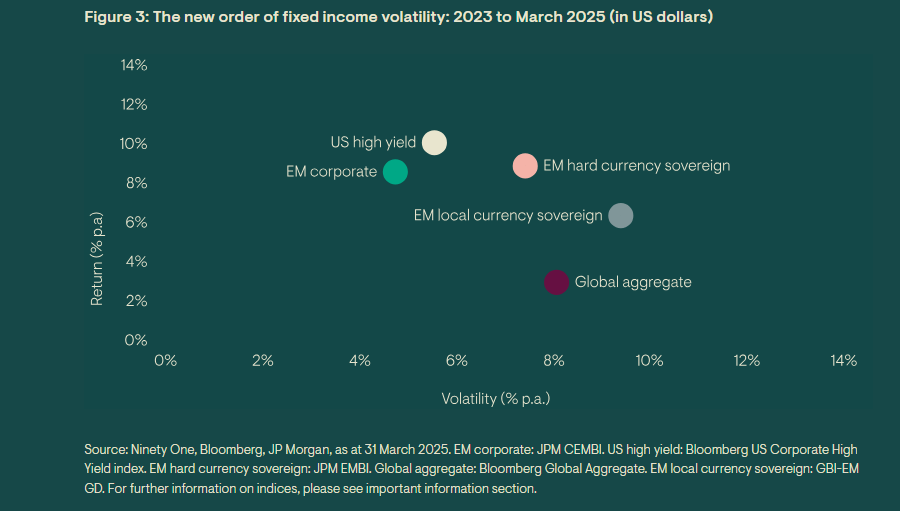

More volatility in the developed market bond space means investors will need to get more return for the additional risk they are taking.

His solution is for investors to turn to an oft-overlooked part of the bond market – the emerging markets (EMs). Here he said perceptions were “outdated” as much has changed from the days of the ‘Brady bonds’ in the 1980s.

Back then, these bonds (issued mainly by Latin American countries) had sky-high yields, liquidity was scarce and most debt was denominated in dollars.

Today, however, Kent said “credible monetary policy” in emerging market economies has underpinned the significant growth of the local currency debt market.

“The volatility of the benchmark has fallen with the inclusion of more Asian markets, with somewhat lower yields today reflecting the higher quality of the asset class,” he noted.

The addition of China and India and the removal of Russia from the index has bolstered this, although investors should keep in mind there are three main cohorts within the market: high-quality Asia; central and eastern Europe; and more cyclical markets

Looking at the Sharpe ratio, Kent said developed market bonds will need to make significantly more in capital gains to match the yields available on their emerging market cousins, as starting yields are higher for EM bonds.

This makes it unlikely that developed market bonds will replicate the historical returns and portfolio diversification that they have in the past.

The next decade “is likely to be more favourable for emerging markets” as the rally in the US dollar “begins to weaken” and structural themes such as deglobalisation, the energy transition and demographics impact investor behaviour.

“Shifts in asset-class behaviour, coupled with the changing nature of economic shocks outlined above, mean the case for portfolio diversification has never been stronger,” he said.

“Crucially, a ‘far and wide’ approach may be needed when diversifying. And this is not just about picking winners; it’s about avoiding losers, especially in today’s geopolitical reality.”

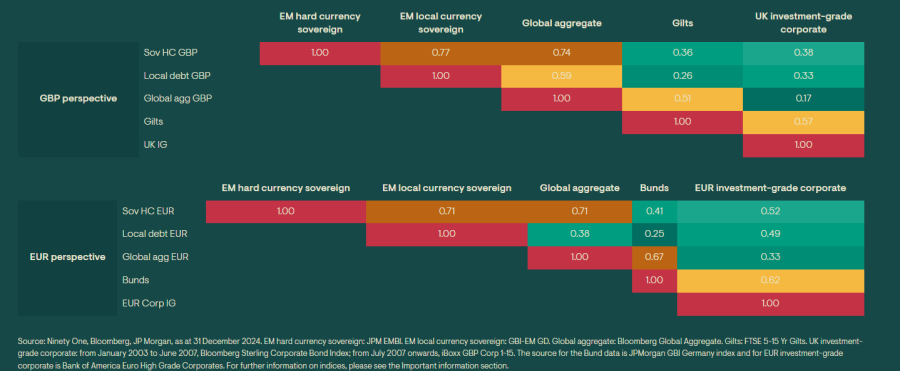

This points to a more diversified global fixed income approach, which includes emerging market debt, something he described as a useful diversifier. This is shown in the chart below, which highlights the correlation of the asset class with other bond markets.

But there is also a benefit from the market’s breadth, with “significant diversifying forces” in the asset class as a whole.

Alongside different countries, Kent pointed out that it spans oil exporters and importers, regional manufacturing hubs and services-driven economies across the globe.

“A key benefit to investing across all EM debt asset classes is that the performance of each sub-asset class is differentiated through the broader economic and monetary policy cycle,” Kent said.

“Supported by an enduring, positive shift in fundamentals, emerging market debt deserves a place at the global investor table.”