The artificial intelligence (AI) super-cycle or bubble – depending on what side of the fence you sit – has unleashed a wave of capital spending that has reshaped global equity markets. But the sustainability of how it’s all being financed is dividing opinion.

A core area of concern is the seemingly circular nature of financing arrangements. For example, Nvidia has invested in AI-focused startups such as OpenAI, xAI, CoreWeave and Inflection. In return, these companies are buying unprecedented volumes of Nvidia’s GPUs.

Nvidia is then recycling equity gains into more investments. And so the cycle continues. Other hyper-scalers, such as Amazon and Microsoft, are doing the same thing.

The argument is that this creates a web of interdependence that could magnify risks if demand or performance disappoints and the bubble pops.

However, Ben Rogoff, co-manager of Polar Capital’s technology and AI funds, said at a recent conference that “the circularity question has been the rallying cry for the bear [but] the reason a lot of people want this to be a bubble is because they are not in it”.

He and other fund managers argue that such deals are necessary to accelerate AI infrastructure buildouts and break through supply bottlenecks.

This debate comes against a backdrop of soaring valuations and earnings growth among the tech giants driving AI investment, which seemingly have the cash on hand to finance the rollout.

Although valuations are higher than many fund managers would like, Robeco research suggests current multiples remain below peaks seen during the likes of the dot-com bubble.

Earlier this month, the US technology sector (which is dominated by the AI-focused Magnificent Seven) was trading at 30.4x forward earnings, compared to a five-year average of 26x and a 10-year average of 22.4x, the research said.

These rising valuations have been supported by earnings growth, it noted, with earnings increasing among S&P 500 constituents by an estimated average of 13.1% year-on-year in the third quarter of 2025. Average earnings growth in the technology sector more specifically was up 27.1%.

Yan Taw Boon, head of thematic in Asia at Neuberger Berman, said it is important that the tech companies with the cash to spare – or hyper-scalers – are using it to build out AI infrastructure and meet growing demand.

“If you look at how the [AI] value chain is structured, companies like OpenAI are leading the way and developing brand new models that need a lot of infrastructure – of which there is an urgent shortage,” he said. “Companies like Nvidia have the cash to invest to deal with these issues.”

However, others like Sean Peche, manager of Ranmore Global Equity, are more sceptical. While the valuations of these US mega-caps “may look reasonable on earnings at around 30x, this balloons to 50x when you adjust for true free cashflow, because capital expenditure far exceeds depreciation,” he said.

When adjusting for this, this leaves investors with a low yield of around 2% – which harkens back to Japan’s equity bubble in 1989, he noted.

He also pointed to the lifecycles of the current chips being made.

“In recent years, tech companies are being clever and moving from depreciating chips and servers from over four years to five years and then six years, which lowers reported depreciation expense and makes profits look better,” he said.

The Ranmore fund is very underweight the US and currently owns none of the Magnificent Seven.

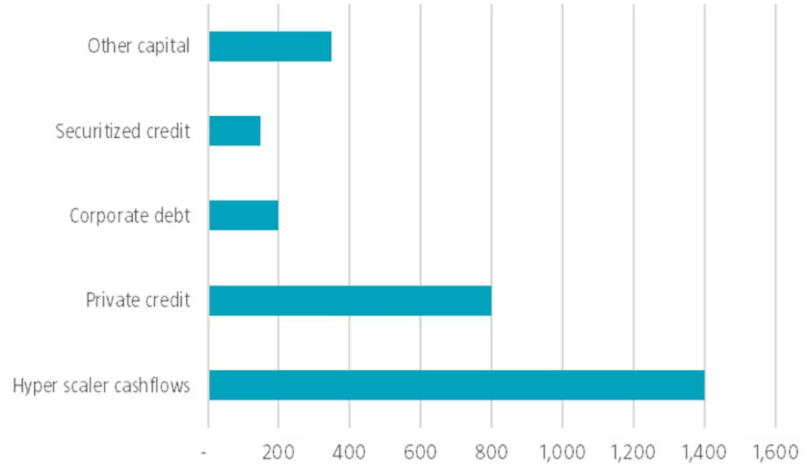

As shown in the graph below, it has nonetheless been estimated that the vast majority of global infrastructure capital investment over the next few years will be funded by hyper-scaler cashflows.

Global infrastructure capital investment by source from 2025 to 2028

Source: Robeco, Morgan Stanley, August 2025

However, a significant portion of the expected investment in AI is expected to come from credit and debt sources, Morgan Stanley said.

This was not a concern for Rogoff, who noted that “the hyper-scalers could create another £1trn in spending through debt if they wanted and they still wouldn’t be overly leveraged – and no one would hold a grudge against them if they did”.

The problem is that not every company in the AI value chain can say the same. Instead, AI start-ups and later entrants to the AI race have little choice but to get creative with financing – forging partnerships with investors and suppliers.

More creative financing structures do pose a new area of risk. The Robeco research noted that private credit arrangements, increasingly structured as special purpose vehicles, enable issuers to raise capital for new data centres via joint ventures without the debt directly appearing on balance sheets.

Oracle is a notable example of a company taking a more creative funding route in the AI race. The US software company has committed to spending hundreds of billions of dollars over the next few years on chips and data centres, largely to make good on a $300bn deal with OpenAI to supply its computing capacity.

It has aggressively tapped debt markets and is nearing $100bn in long-term debt, with some analysts like Morgan Stanley forecasting this will hit $290bn by 2028.

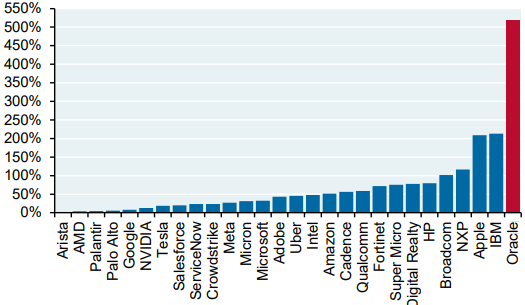

The company’s debt-to-equity ratio has surged to 500% compared to 50% for Amazon, 30% for Microsoft and even less for Meta and Google.

Debt-to-equity ratios of direct AI stocks

Source: JPMAM, Bloomberg. Data as at 16 September 2025

We have also seen the possible risks of this approach play out in real time.

Earlier this month, Oracle’s share price plunged by around 25% due to AI cost concerns, debt financing, thin cloud margins and slower growth, reversing more than $250bn of gains in its market value follows its initial announcement of the OpenAI deal in September.

Andrew O’Brien, manager of the US-domiciled Putnam Global Technology fund, said he is “bullish on AI” but noted it makes sense that there is “healthy investor scepticism about the circular nature of some of the financing”.

With regards to Oracle, he said the company has “less fungibility” than the likes of Microsoft, Amazon and Google.

“You have to hope that the leverage comes down over time but the scepticism is reasonable, as [Oracle] is dependent on a single client deal with OpenAI and is needing to take on a significant portion of leverage which simply isn’t required by hyper-scalers.”

S&P Global has warned that a third of Oracle’s revenues will be tied to OpenAI by 2028.

Too much dependence on another company is a risk fund managers will need to account for as they continue to explore investment opportunities in the AI race.

As such, O’Brien said he has been reviewing companies’ degrees of reliance on AI-focused businesses like OpenAI – whether it be through joint ventures, equity partnerships or large supplier contracts – to make sure he understands which businesses have a forward trajectory in their revenue and earnings power and which are most reliant on another company’s future success.

“It is structurally important for us now to be tracking the success of companies like OpenAI and Anthropic, which have become such an important part of the demand drivers for other businesses,” he said. “Their success or otherwise is going to be highly impactful.”