Buy-and-hold investing is facing one of its most searching tests in years, according to experts, as rising rates, volatile sector leadership and shifting valuations challenge the assumptions that powered its decade-long success.

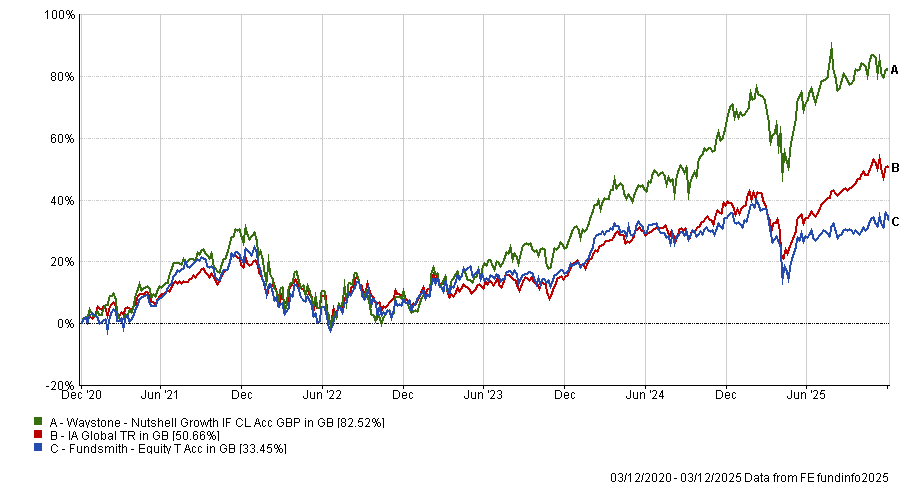

Terry Smith’s Fundsmith Equity – often held up as the model of the low-turnover quality style – enjoyed exceptional returns in the 2010s, but its performance has weakened in recent years. Meanwhile, higher-turnover approaches such as the Nutshell Growth strategy have found far more fertile ground in today’s stop-start market cycle, as the chart below shows.

Performance of funds against sector over 5yrs

Source: FE Analytics

As investors reassess whether the old playbook still works, Stonehage Fleming’s Gerrit Smit has already warned that the traditional buy-and-hold mentality “is more dangerous now”, even for managers committed to it.

“It’s more dangerous now to just buy and hold, but that’s what our mandate is,” he said. “We call it ‘buy to hold’, because we have the intention to hold the names we have, but if facts change, we change our mind.”

Below, Trustnet explores whether investors should change their minds too when it comes to buy-and-hold strategies.

Why buy-and-hold thrived and why it has stalled

Buy-and-hold strategies such as Fundsmith Equity and Lindsell Train Global Equity were built for the era of disinflation that followed the global financial crisis. Ultra-low rates compressed discount rates, while quantitative easing flattened economic cycles and rewarded companies that could compound steadily over long periods.

Simon Evan-Cook, manager of Downing’s fund-of-funds range, said: “During the quantitative easing era, it made sense, certainly with hindsight, to find the winners and just stick with them”. But the return of inflation, and then rising interest rates in 2022, brought the return of an economic cycle and much more dispersion.

With markets rotating sharply between winners and losers, long-duration strategies have struggled to keep pace.

“It doesn’t help Smith that, because that was such a good strategy, for 10 years all the valuations of his stocks went up to very, very high levels,” Evan-Cook said. “He probably overachieved in that 10-year period, which is why, over the past five years, he’s underachieved.”

The rise of the high-turnover style

In contrast, higher-turnover strategies – which seize on short-term valuation dislocations and move quickly as market leadership changes – have flourished in these conditions, with the difference in duration being decisive.

“Both of those can be perfectly good strategies, but shorter duration seems to be working better at the current time, because you’ve got more volatility to move into and out of,” Evan-Cook said.

Some of his preferred strategies buy cheap stocks and then wait for it to recover over three to six months, before selling and moving on to another cheap stock.

These include Mark Ellis’ Nutshell Growth, which achieved the maximum FE fundinfo Crown rating of five through an “eye-popping” portfolio turnover, and Sean Peche of Ranmore Global Equity, which recently outperformed without owning any of the Magnificent Seven.

Their skillsets are rare, however, because over the previous 10 years, “a lot of what those manager did didn’t work and so they probably lost their jobs or lost interest”.

The survivors are now benefiting from a market that once again rewards faster decision-making.

Even so, Evan-Cook remains balanced, believing low-turnover quality strategies like Fundsmith Equity still make sense for medium-to-long-term investors. In fact, he said that “today is a better time to buy that style than five years ago, because valuations have reset”.

However his favourite fund in this space isn’t Fundsmith Equity but Evenlode Global Equity.

Buy-and-hold is not dead

Rupert Silver, director at Credo, said the key is not the philosophy but the underlying businesses. “It’s true that investors could buy world-class businesses at unusually cheap levels and hold for exceptional returns, but the above quote refers to a unique moment in history.”

Still, higher valuations today do not make buy-and-hold wasted capital as quality businesses with durable advantages can still compound value, albeit from less attractive starting points.

However, Silver noted a structural challenge: only around 30–40% of companies outperform the market in a typical year. This makes it difficult for managers to beat the index by simply holding a basket of stocks and has contributed to the rise of low-cost passive funds.

Buy-and-hold or buy-and-hope?

Similar considerations apply when picking funds, with Dennehy Wealth discretionary investment manager Joe Richardson drawing a sharp line between discipline and inertia.

“There’s a big difference between buy-and-hold as a discipline and buy-and-hope,” he said. “Many investors adopt the latter without realising it, holding onto funds long after the evidence has changed.”

Richardson stressed that buy-and-hold only works when valuations are sensible at the starting point. “That was true coming out of the global financial crisis… but we’re now at a very different starting point. A fund that worked brilliantly then doesn’t automatically work now.”

He pointed to the collapse of former star manager Neil Woodford’s eponymous investment firm as an extreme example of the danger: investors who “bought and held” did not merely underperform but were trapped in a suspended fund.

His team’s research found that around 95% of funds fail to deliver consistent outperformance over time, underscoring how difficult it is for any buy-and-hold approach to deliver reliably without ongoing scrutiny.

Buy-and-hold, he concluded, “is not dead”, but treating it as a universal rule for all market conditions “is where investors can run into trouble”.