The global financial crisis ushered in a new era of central bank intervention and quantitative easing, followed by colossal monetary stimulus during the Covid-19 pandemic, the impact of which is still being felt throughout financial markets. Ben Leyland, who manages JOHCM Global Opportunities with Robert Lancastle, believes the strong performance of some global equities has caused people to forget hitherto accepted beliefs such as the importance of diversification.

He thinks the investment environment prior to 2007 was much more ‘normal’ but “a lot of people have never worked in a ‘normal’ investment environment”, which has led to complacency and lack of understanding about risk.

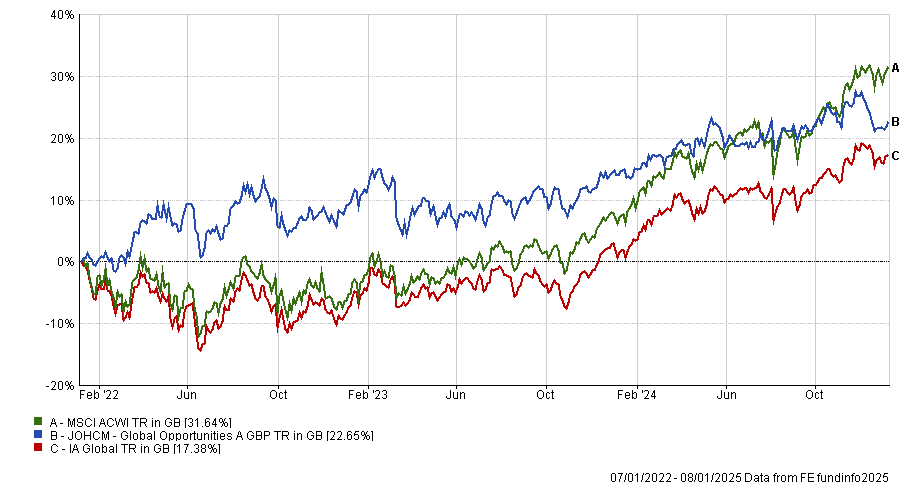

Leyland has over 22 years of investment experience, having joined JO Hambro Capital Management from Schroders in 2006, and has managed JOHCM Global Opportunities since June 2012. The fund has delivered a second quartile return of 22.7% over the past three years.

Fund performance over 3yrs

Source: FE Analytics

Below, Leyland explains why the Magnificent Seven are not bulletproof companies, why the past two years have caused investors to forget the need for diversification, and how investors have become more complacent.

What is your investment strategy?

We aim to achieve above-average returns with below-average volatility by combining a quality bias with consistent through-cycle risk controls and a strict valuation discipline to minimise downside volatility.

We define quality quite broadly and that means we can look for underappreciated and misunderstood situations of compounding quality and growth, often in less popular parts of the market. As a result, we have a concentrated, benchmark-unaware portfolio that is likely to evolve through time.

Why should investors own your portfolio?

In 2022, everyone remembered the importance of diversification and realised that most of their holdings were facing in the same direction. Yet we have forgotten those lessons because 2023 and 2024 have told investors that the last thing you need to do is diversify away from the Magnificent Seven. But we think it is always worth reminding people of the importance of diversification and complementarity within your portfolio.

Are there any challenges with being a quality investor with minimal exposure to the Magnificent Seven?

There is a misperception that the only place to find quality is in the Magnificent Seven. For us, certain members of the Magnificent Seven do not pass our quality tests. For example, Meta is not a business we spend much time analysing. It could be a tremendously powerful business in 15 years, but it could also not exist because consumers tend to be fickle.

It goes back to that definition of quality. It has become too common to group quality and growth together and define quality purely in relation to 10-year performance. So, there is a misconception that these businesses are bulletproof and valuation is limitless. But over the past three years, you could find good quality from real-world companies, exposed to much-needed investments such as infrastructure.

I just do not think it is true that the only place to find quality and growth is in the US and tech.

What was your best-performing holding over the past year?

The best contributor was CRH, up by 42%. It is a construction business that historically was Irish-listed but primarily exposed to US infrastructure. They relisted in the US just over a year ago and have continued to perform well since.

It’s a business with good pricing power exposed to an ongoing cycle of infrastructure renewal, including but not limited to highways in the US. On top of this, the management has a great track record of deploying capital into mergers and acquisitions to consolidate the sector.

And your worst?

Most of our worst performers have suffered from a post-Covid destocking cycle – businesses that went through a bust and boom and then bust again after Covid. The main example was Infineon Technologies, a German semiconductor company with a bias towards industrial and automotive semiconductors, which was down by 17%.

These are not the kind of semiconductors that go into data centres, they go into cars and factories, and that market is going through a period of weakness. But crucially, we think that is temporary, not structural. Infineon is well placed for the long-term rising penetration of semiconductors in those end markets.

What is the biggest investment lesson you learnt in your career?

The world evolves, but human behaviour goes in cycles, so a lot of people have never worked in a ‘normal’ investment environment. Because of that, I think there are a lot of misperceptions about risk, portfolio construction, how to create value over the long term and the importance of risk controls.

The lesson we have all learnt over the past 15 years was to buy the dip. But if you look at the period between 1999 and 2009, there were two major drawdowns and markets were flat, and so it has been a more uncomfortable period to invest in equities and risk controls are much more important than they have been since.

Cyclical behaviour is kind of generational. When most people in an industry have not seen the last proper downturn, which was the GFC, you start to get complacency and a lack of understanding about where risks lie. There is such a thing as an investment cycle.

What do you do in your free time?

I go for mountain walks with my kids and bike rides around the South Downs.