Emerging markets (EMs) have underperformed developed markets for one reason and one reason only: dilution. That is the view of Varun Laijawalla, manager of the Ninety One Emerging Markets Equity fund, who said this phenomenon could finally be turning around.

Dilution describes the financial headwind created as emerging market indices ballooned with new listings, eroding the value of existing holdings. He argued that the decisive drag on returns over the past 15 years has been net issuance – how much a market’s share count grows after initial public offers (IPOs) and buybacks – not growth, margins, valuations or currencies.

With issuance collapsing and companies shifting towards buybacks and dividends, that headwind is now fading and could soon become a tailwind. Laijawalla said emerging markets did not lag because their companies grew more slowly or became less profitable, but because waves of IPOs and index inclusions, particularly in China, expanded the benchmark faster than earnings.

“Lots of IPOs, lots of index inclusion, a lot of net issuance, particularly in China – that is the fundamental financial reason EM equities have underperformed the US and developed markets,” he said.

He believes the turning point is tied to “the year of change”. After a decade in which the US dominated returns, that pattern broke this year: emerging market equities rose around 35% versus 20% for developed markets, the dollar reversed its 15-year climb and several EM countries – notably China and Korea – made meaningful policy shifts.

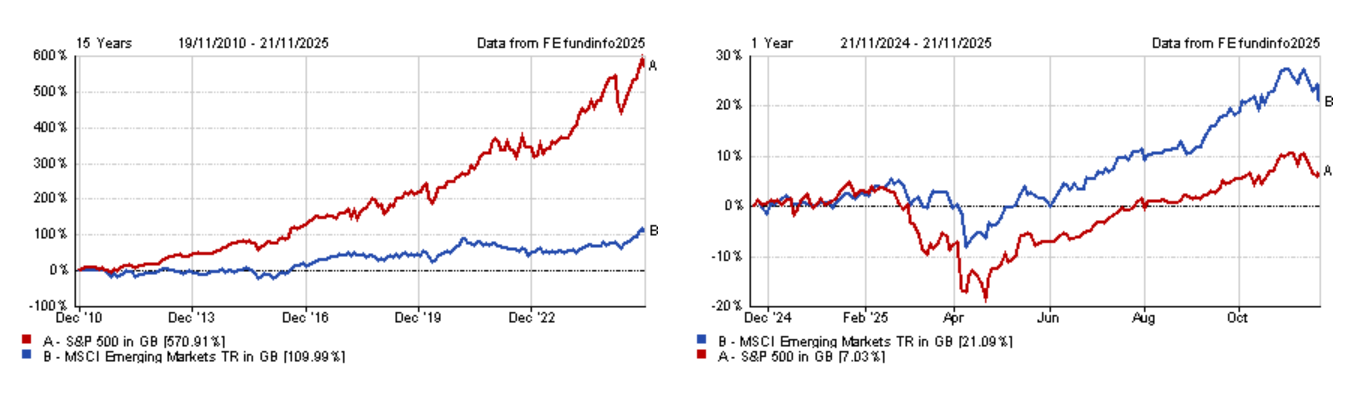

Performance of indices over 15 and 1yr

Source: FE Analytics

In China, he highlighted two developments that reset sentiment. The emergence of DeepSeek challenged the idea that Chinese innovation was dead. Soon after, president Xi Jinping met 25 private-sector entrepreneurs, placing his arm around Alibaba co-founder Jack Ma. “It was an enormous signal to the market,” said Laijawalla.

Equally important is how companies are behaving. After years of issuing shares, Chinese corporates are shrinking share counts and returning cash. Buybacks last year hit record highs, double the year before, and dividends followed a similar pattern.

Chinese entrepreneurs, unable to control geopolitics, regulation or consumer behaviour, are focusing on what they can influence: capital allocation.

“The corporates’ view is: ‘The only thing I can do is control the capital that flows through my business, therefore, I will buy back my own stock and pay out a dividend’. That is an enormously powerful driver that is potentially going to lead to that headwind – net issuance – becoming a tailwind.”

In Korea, meanwhile, a new government with a parliamentary majority acted quickly on corporate governance reform. “If you are tackling the major issue with that market, clearly that’s a huge positive change in direction,” he said.

Despite this brighter backdrop, concerns linger. Concentration risk has dominated debate this year, and not just in the US.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), an 11% benchmark heavyweight, is central to both EM indices and global supply chains. While some investors try to sidestep that exposure, Laijawalla argued that avoiding it introduces more risk than owning it.

“I need to own TSMC whether I like it or not – and we’re comfortable with that risk. If I hold none of it, then I have an 11% active weight in one stock. It doesn’t matter what the other 79 stocks do; how I perform will be down to one stock. That’s not what we’re trying to do.”

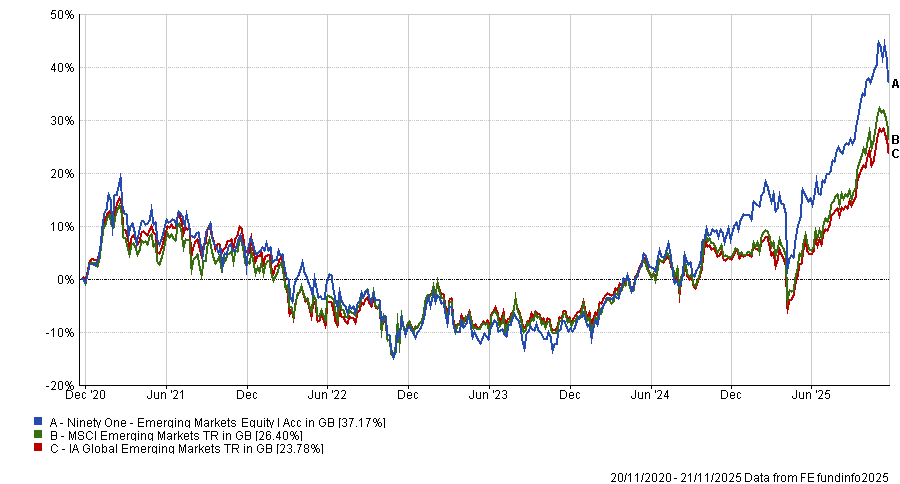

Performance of fund against index and sector over 5yrs

Source: FE Analytics

This feeds into another point: investors should not fight survivorship bias within EM. Index concentration rises when winners pull ahead, and capping those weights may feel prudent but can undermine returns. “If the company does well, it’s a bigger part of the benchmark.” Penalising structural winners, he argued, is a mistake.

For passive investors, the implications are sharper. Today’s emerging market index construction leaves passive holders with roughly 30% in the top 10 stocks and 20% in the top five.

Combined with falling issuance – which widens the gap between companies that can self-fund and those reliant on capital markets – the backdrop is far tougher for passive ownership.

“The dispersion between good companies that are able to fund their own growth versus those that are serial issuers widens. As active investors, that’s our dream,” he said.

A further barrier for global allocators is the influence of powerful political leaders. “A defining characteristic of emerging markets is the weakness of institutions and the strength of the strong men and women that run those emerging markets,” he said.

Laijawalla acknowledged the concern but argued that markets respond to change, not absolutes. When leadership shifts from very negative to less negative, capital tends to follow. That dynamic, he said, explains why China – which few expected to outperform this year – became one of the best-performing emerging markets.